Sometimes we either want to dive deep in the sound, enjoy privacy or avoid unnecessary social attention to unconventional music emotion. Headphones-first listening was historically the main scenario for a number of non-mainstream genres: black metal, psybient, dungeon synth, but today approximately 71% of headphone owners primarily use headphones for music listening, with streaming reaching 4.8 trillion streams globally in 2024 - that signals about the changed habit across popular music listening (1 and 2).

Let’s compare two mixing scenarios:

My album sounds its best on the stereo system, and pretty good on headphones.

vs.

My album sounds its best on headphones, and pretty good on the speakers.

Traditionally most of us chose the first variant while working with audio. But should we follow this logic now, given the information on the changed habit?

To answer this question, I want to go a bit deeper into the following: what can headphones do that speakers physically cannot? And more importantly - how do we design our mixes to exploit these unique capabilities? In today's article I explore the process of creating music specifically designed for headphone playback.

The Headphones Difference

Headphones offer several features over any speaker system.

Intimate proximity means the drivers are millimeters from our eardrums, creating detail resolution that requires treated room and speakers costing tens of thousands of dollars to approach. Every breath, every texture is preserved without room reflections smearing the information.

Perfect channel separation means zero acoustic crosstalk between left and right channels. With speakers, sound from the left speaker bleeds into our right ear and vice versa. With headphones, we have complete control over what each ear receives independently

Extended sub-bass response is one more important difference - even modest headphones can reproduce frequencies below 30Hz that most home speaker systems physically cannot generate. The proximity to our eardrum means bass doesn't need to move large volumes of air to be perceived.

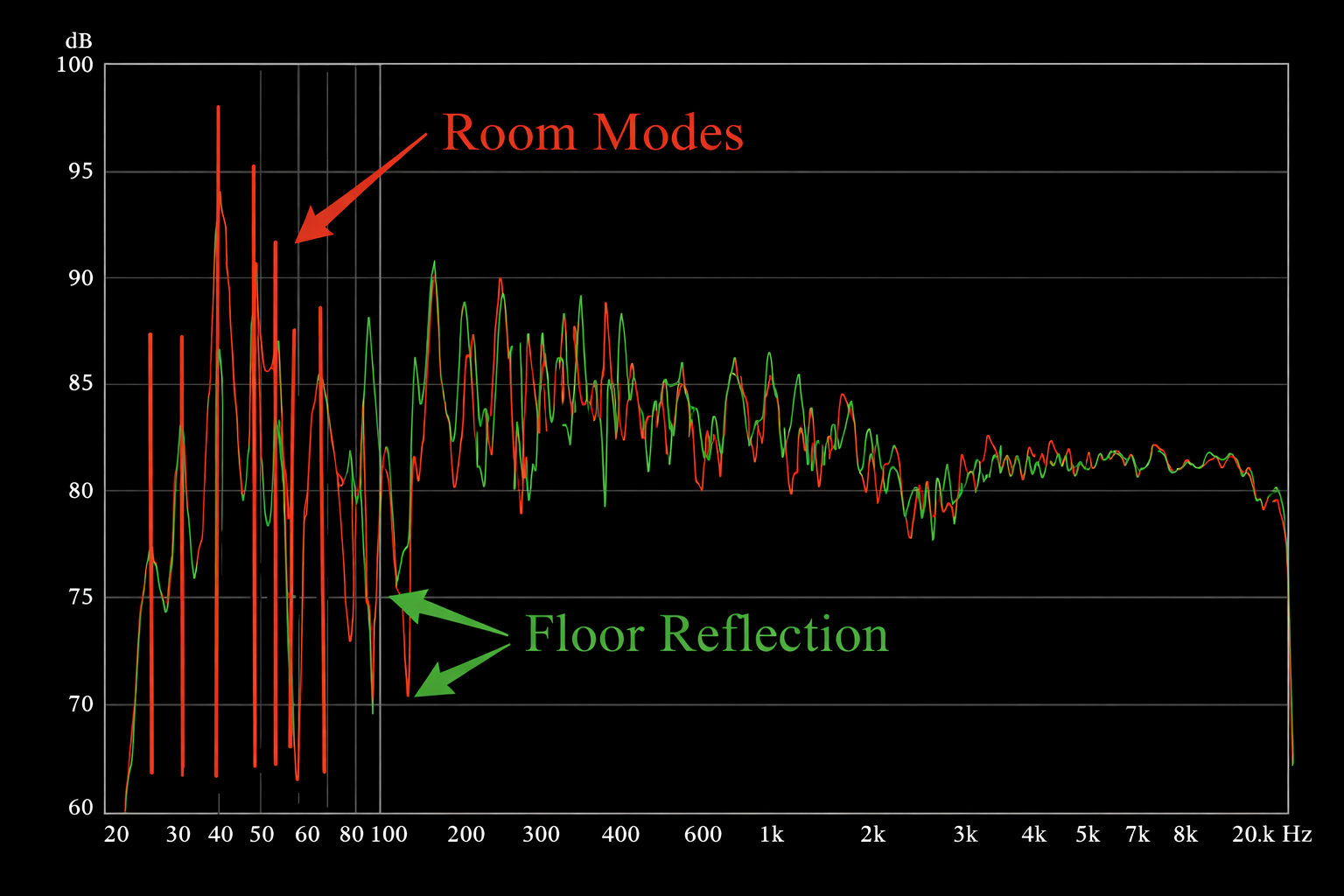

Eliminated room acoustics is normal case, with no standing waves, bass nodes, flutter echoes, untreated early reflections colouring our sound. The sound goes directly from driver to eardrum without any acoustic environment interfering.

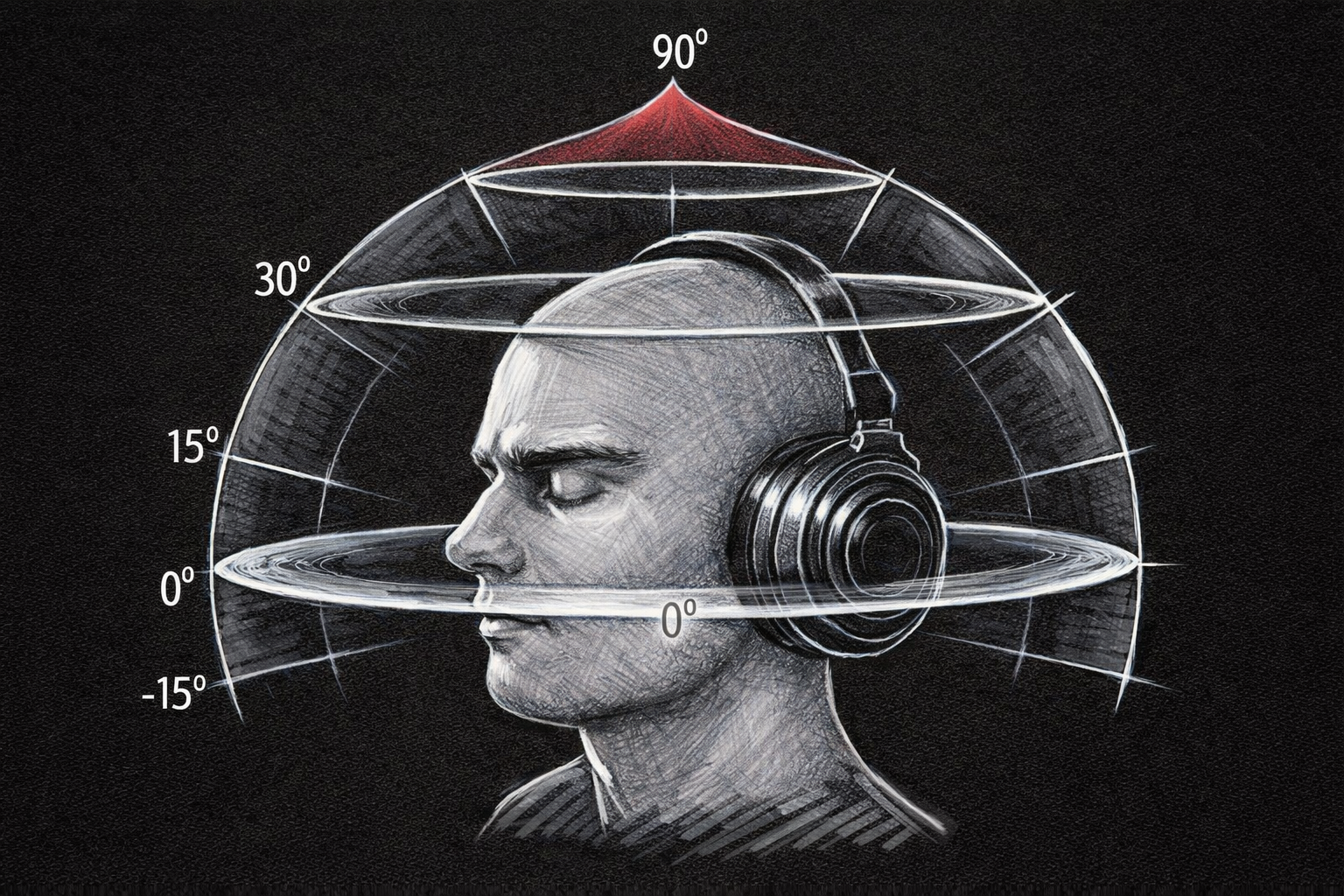

3D spatial positioning through binaural techniques and HRTF processing matured rapidly in gamedev industry, headphones can place sounds behind us, above us, and at precise distances. Speakers can only create phantom images between the speaker positions in front of us.

What sound engineering body of knowledge suggests we can do?

Extreme stereo width is possible and pleasant

On speakers, extremely wide stereo creates problems. Phase relationships cause sounds to partially cancel in mono, and very wide elements can feel disconnected from the center image. You're constantly balancing "how wide can I go before it sounds wrong on speakers?" With headphones as primary target, you can alter the approach.

The professional approach uses several techniques:

Mid-side processing for controlled width, that applies wide stereo enhancement specifically to your side component while keeping the mid channel focused and mono-compatible. This creates massive width without destroying the fundamental structure of your mix. In ambient music production, mid-side EQ is particularly powerful - you can boost atmospheric frequencies (8kHz-16kHz) exclusively in the sides, creating sense of infinite space.

Frequency-dependent stereo width where the low-end (below 150Hz) stays not wide for power and focus. Your mids (150Hz-8kHz) use moderate width for instrument placement. Your highs (above 8kHz) spread extremely wide for "air" and spaciousness. Multiband stereo imaging plugins let you apply different width to different frequency bands independently.

Haas effect for extreme stereo perception by duplicating a sound and delay one side by 1-25 milliseconds. The original appears where the first sound arrives, but the stereo image becomes impossibly wide. On speakers this can create odd phase artifacts, but on headphones where each ear receives completely isolated signal, the effect is spectacular.

The classic contrast between narrow and wide elements creates the perception of vast spatial depth that headphones excel at revealing. For ambient and atmospheric black metal where soundscapes are primary focus, this freedom to create extreme width without worrying about speaker translation is liberating.

Binaural production for spatial effect

Binaural audio for headphones can create sound that appears to come from anywhere in full 360-degree sphere around your head - behind you, above you, below you, at specific distances (3). Recent research with 140 practitioners found that genres like electronic dance music, jazz, classical, and ambient are particularly suitable for spatial audio mixing (4)

I didn't know that the Dolby Atmos Renderer includes binaural mode specifically for headphone mixing, with new "Broadcast" mode optimized for headphone listening quality. You can place individual audio objects anywhere in 3D space and the renderer converts it to two-channel binaural audio.

The other tool I discovered recently for this purpose is L-ISA Studio, that allows object-based 3D mixing on headphones with binaural rendering. The free version includes binaural mixing, specifically designed for creators working primarily in headphones.

For atmospheric black metal or dark ambient, imagine placing ritualistic chants behind the listener, having synth pads rotate slowly around their head, positioning distant thunder above and to the left at specific distance. These spatial movements are simply impossible with traditional stereo speakers, but trivial with binaural headphone mixing.

ASMR beyond adult entertainment

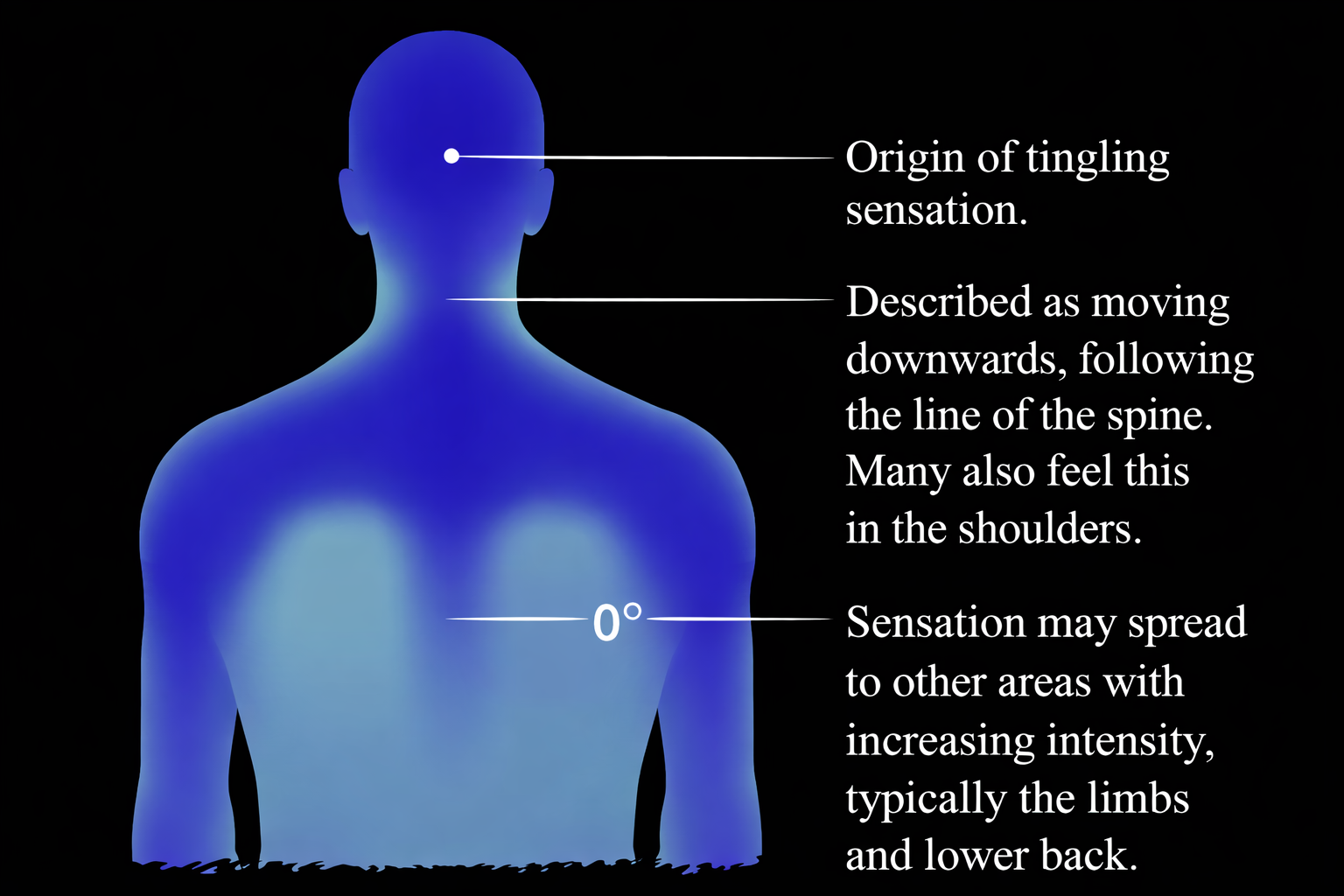

In my opinion most emotionally powerful advantage of headphones - the sense of intimate proximity of whispered word or quiet vocals. ASMR (Autonomous Sensory Meridian Response) content has fully embraced this, but the technique is equally powerful for music production in ambient, intimate folk, atmospheric black metal, and experimental electronic genres.

ASMR provides an experience of "low-grade euphoria" which features combination of "positive feelings and a distinct static-like tingling sensation on the skin". This can work well in the genres which focus on deep sensual experiences.

When you record vocals with close-miking technique (2-4 inches from capsule) and mix them specifically for headphone playback, you create sensation of the vocalist whispering directly into the listener's ear. This level of intimacy is physically impossible with speakers, where the sound source is always positioned meters away from the listener. Use pop filter to manage plosives, but don't eliminate all breath sounds - these become part of the intimate character. For maximum intimacy, use stereo pair or binaural dummy head for vocal recording. This creates natural sense of space and allows subtle panning of whispers and mouth sounds from left to right ear, dramatically increasing immersion.

Be careful with processing to preserve detail: light compression (2-4 dB gain reduction) to even out dynamics without destroying the natural breath and texture. Subtle de-essing if needed, but be careful not to over-process and lose the organic quality. The goal is to preserve every intimate detail that headphones can reveal but speakers would blur. Using binaural panners (available in most spatial audio tools), you can position whispered vocals slightly behind and to the side of the listener's head, creating sensation of someone leaning close to speak privately. This positioning is impossible with traditional stereo panning.

The contrast is stark: on speakers, intimate whispered vocals often get lost or sound inappropriately quiet. On headphones, they create powerful emotional connection - one of the nicest examples comes from modern pop music with the album "When We All Fall Asleep, Where Do We Go?" by Billie Eilish.

Sub-bass contains tasty details

Quality headphones often provide more accurate and extended bass response than most home speaker systems - sad physics of untreated houses we live in. Speakers need to move large volumes of air to create bass frequencies, especially below 60Hz. Small to mid-size monitors physically cannot generate true sub-bass (20-40Hz) at adequate levels. Even if they could, room acoustics create standing waves, bass nodes, and cancellation zones that make low-end wildly inconsistent depending on listening position.

Headphones bypass all of this by design: don't be afraid to add sub-bass content down to 25-30Hz. In ambient and psybient, these ultra-low frequencies create physical sensation and emotional weight. In atmospheric black metal, sub-bass drones under distorted guitars add crushing heaviness that disappears on smaller speakers but dominates on headphones.

Detailed bass texture and movement is important difference from speaker-first records. On speakers, bass frequencies naturally sum to mono due to room acoustics and crossfeed. On headphones with perfect channel separation, you can create subtle stereo movement in bass (60-120Hz) that reveals bass guitar string articulation or synthesizer filter modulation that would be completely lost on speakers.The detail resolution of headphones also lets you layer multiple bass elements (kick, bass, sub-bass pad, low-frequency drone) without them turning into muddy soup. Even tiny EQ adjustments that create separation are clearly audible on headphones.

Tip: reference this part with closed-back headphones that have good low-end extension. These designs provide more accurate bass than open-back models for critical low-end decisions.

Spatial clarity: layered binaural reverbs

Depth in traditional stereo mixes is created primarily through relative volume (louder sounds feel closer), reverb amount (more reverb feels more distant), and EQ filtering (bass/highs). These techniques work, but they're limited to front-to-back depth perception between the speakers.

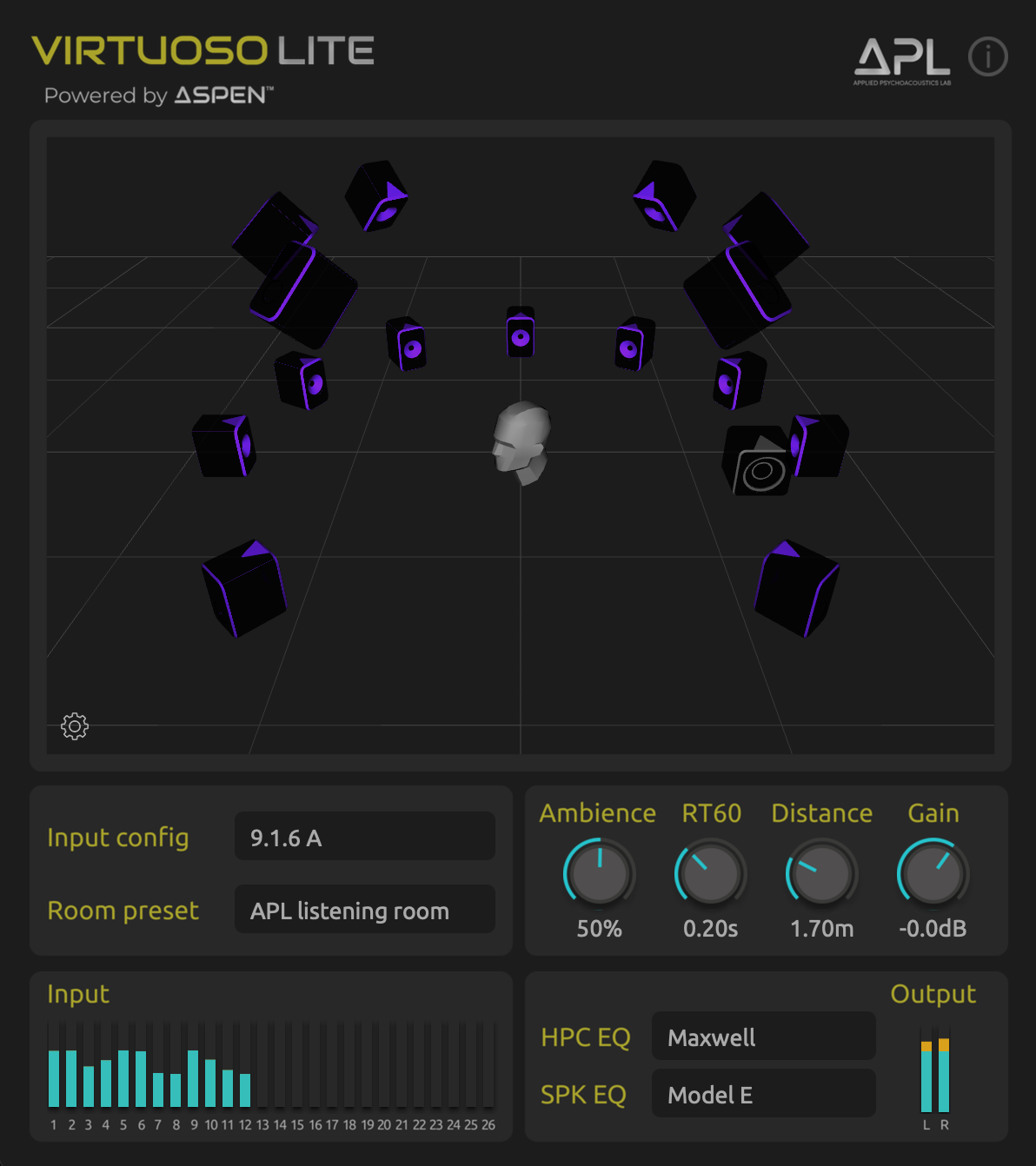

Binaural reverb with distance simulation tools like APL Virtuoso, Lewitt Space Replicator, and Waves Nx simulate the acoustic behaviour of sound at different distances from the listener.

A sound positioned 2 meters away has different spectral content, reverb character, and direct-to-reverberant ratio than a sound 10 meters away. Create multiple reverb sends, each processed with binaural room simulation at different listener distances. Send pad sounds to far reverb (8-10 meters), rhythmic elements to medium reverb (3-5 meters), and featured elements to near reverb (1-2 meters). On headphones, these will position themselves at perceptually different depths automatically.

Using Dolby Atmos or other spatial audio tools, position atmospheric elements above the listener's head. Rain, wind, distant drones can occupy the overhead space that doesn't exist in traditional stereo. In my opinion, this vertical dimension is one of the most effective uses of spatial audio in music production.

Movement through depth is another level of mix liveliness - it's not difficult to automate binaural position so sounds move toward or away from the listener over time. A synth pad that starts distant and slowly approaches creates emotional intensity impossible with traditional automation. Fun part, contrary to the speakers, this movement is physically perceived on headphones. For ambient music specifically designed for headphone listening, these depth layers create extraordinarily immersive soundscapes.

Contrasting intimacy and space within single mix

This principle synthesises several previous points into cohesive approach: headphones let you simultaneously present elements with intimate proximity AND vast spatial width in ways that contradict each other on speakers but coexist beautifully on headphones. I found the following observations that are reproduced from session to session in ambient music:

- Intimate center with vast periphery. I place primary vocal or lead element with intimate, close-miked character in center. Simultaneously, I spread atmospheric pads, reverb tails, and textural elements to extreme width and distance. The trade-off I'm aware about and accept: on speakers, the intimate close sound would conflict with the distant wide sound as a not well-understood weird decision. On headphones, they occupy different perceptual spaces and enhance each other through beautiful contrast.

- I use mono to anchor for width perception - classics of mixing. This is strategic choice that makes wide stereo elements feel impossibly vast by comparison. To perceive width, we need reference point.

- As headphones eliminate acoustic crosstalk entirely, I use this to create frequency-dependent width that builds sense of spaciousness without muddying for the different instrumental buses. Izotope's Ozone Imager works perfectly for exact this purpose, and I highly recommend it as a working horse solution.

- Elements can move in stereo field more dramatically on headphones without sounding unnatural. Auto-panning sweeps, binaural rotation effects, and dramatic left-right movements work beautifully on headphones (and the tradeoff is it often sounds gimmicky or nauseating on speakers). The decision is important.

Preserving detail that speakers would destroy

My final principle is about what not to do. When mixing primarily for speakers, we make compromises to accommodate room acoustics, speaker limitations, and listening distances. When mixing for headphones, many of these compromises are counterproductive.

The proximity of headphones reveals every attack transient, breath, etc. On speakers, these details get blurred by room reflections and air absorption. For headphone mixing, I like to preserve these micro-details rather than over-compressing them away. Headphones can reveal 24-bit dynamic range that speakers in imperfect rooms cannot. I don't like compression applied much in my mixes - I simply don't need to over-compress to compensate for difficult listening environments. Subtle dynamics are perceptible and praised by the headphone audience, so this is a different approach to mixing that is controversial to modern industry.

One more example, content above 12-15kHz often gets a bit rolled off for speaker playback because room acoustics and speaker limitations make it harsh. On quality headphones, these frequencies provide beautiful air and spaciousness. I love to preserve them.

The counterintuitive insight for me was mixing for headphones often means doing less processing. The clarity and detail resolution means you don't need heavy-handed EQ, aggressive compression, or artificial enhancement to make elements cut through the mix. Subtlety works on headphones in ways it cannot on speakers in typical rooms.

Mixing for headphones?

There is resistance in professional audio community to the idea of mixing for headphones rather than just mixing on headphones. The traditional workflow - mix on speakers, check on headphones - is deeply ingrained. And for certain applications, it remains absolutely correct.

But for ambient music, experimental electronic genres or more extreme genres like atmospheric black metal where the audience is overwhelmingly using headphones, this traditional approach is backwards. We're optimising for the minority playback system (speakers) while compromising the experience for the majority playback system (headphones).

Mixes optimised for headphone listening may not have the same impact on large speaker systems. Extreme stereo width that sounds spectacular on headphones can have phase problems when summed to mono for club PA systems. Intimate whispered vocals positioned binaurally might sound odd on speakers. Ultra-extended sub-bass might not translate to small Bluetooth speakers. But here's my final question: what percentage of your actual listeners will experience those speaker playback scenarios?

For most of listeners in the genres I work with, the answer is clear. They're on Spotify or Bandcamp through their headphones at 11pm, seeking immersive escape from daily reality. They want the intimate, detailed, spatially vast experience that only headphones can provide. Young listeners don't even own speaker systems - their music consumption is entirely through headphones and earbuds. And major streaming platforms of 2025 like Apple Music and Tidal actively promote spatial audio content optimised for headphones.

For us creating atmospheric, immersive music in niche genres, this shift is opportunity. We can finally design mixes that exploit the unique capabilities of headphones - the 3D spatial positioning, the intimate proximity, the extended bass, the extreme width, the micro-detail resolution - without compromising for speaker playback that most listeners won't use anyway.

The tools exist, and the audience exists too. Even the professional acceptance already exists. What remains is creative courage to fully embrace headphones as primary medium and explore the sonic possibilities that speakers simply cannot achieve. Let's go?